Mis-diagnosing Virtual Collaboration

.jpg?width=50&name=TS%20Hollema%20-%20Copy%20(2).jpg) Theresa Sigillito Hollema

·

3 minute read

Theresa Sigillito Hollema

·

3 minute read

Sometimes looking from a different angle makes the difference.

For years I have pondered the key ingredients to make an offshoring structure in a company a success. By offshoring I mean the centralisation of a function in one location (ie., Shared Service Center, Center of Excellence, R&D Center) with internal customers or colleagues around the world. Fifteen years ago I attended a presentation at a global IT company about their own offshoring experiences. Their developers and programmers were in India, and the sales and marketing were in different countries in Europe. The presenter described their experience and listed fifteen problems, twelve of them which were related to cultural differences. I thought that if everyone develops their cultural competence, all will be well.

But as I discussed these structures and the ongoing issues with clients and colleagues, I felt there were more factors involved to explain the weak collaboration between the centralised location and the global colleagues. I found another piece to the puzzle when I read the work of Maynard and Gilson, who looked at the types of virtual teams and the necessary levels of communication for success.

Bell, Kozlowski

Bell, Kozlowski

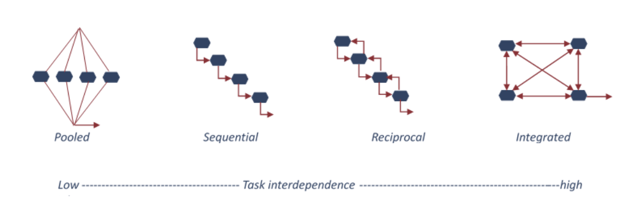

Blue block = person; Red line = communication/information flow

To start, they identified four types of virtual teams, based on the degree of interdependence of the team members in order to complete the work. In other words, how much must the team members work together? In Pooled teams, each person works independently, but they agree on the output at the end. Team members in Sequential teams define the output of one person which becomes the input for the next person. For example, someone prepares a local finance report and sends it to the regional consolidator at headquarters. In Reciprocal teams, the output and input are not standard, and require a conversation between people in different locations. For instance, an IT company in which the local sales team describe to the developers in India the specifications for the customised customer solution. The team in India would send demos and ask questions in an iterative process. In Integrated teams, the team members are fully interdependent in how they work, share information, and complete the output together. For instance, a multi-functional customer support team.

Here’s the problem – many centralised offshore structures think of themselves as sequential when they are really reciprocal. They think in terms of separation – ‘they do their task, we do our task’. This mistake is understandable. The actual distance, collaboration technology and service level agreement set the conditions for the colleagues to think of themselves as very detached from the others.

The result is the following scenarios:

- Co-located. If the colleagues were in the same location and one received a report that was confusing, she would walk down the hall and speak with her colleague. They would share their understandings and resolve the issue.

- Virtual, acting as sequential. The internal customer receives a report that she requested and thinks the task is complete. She is dissatisfied, frustrated and complains to her local colleague. If she did have the inclination to contact the report creator, she hesitates because she does not know the person, is wondering about the cultural communication minefield, and struggles to use the appropriate technology. The creator of the report is wondering why he only receives complaints, instead of instruction or advice. He does not contact the report requestor for similar reasons - too many unknowns.

- Virtual, acting as reciprocal. If someone receives a report that is confusing, she contacts her remote colleague who she knows well and they resolve the issue. She effectively uses the communication technology and has the cultural understanding to successfully communicate. She is not talking to a stranger, but to a colleague who she knows has the same shared goal. Her remote colleague sends a revised report and she is satisfied.

Team members on high-functioning reciprocal teams view the collaboration as relational and invest the time and energy to build the connections and communication pathways across the distance. They do not think in terms of hand-offs, but in terms of interaction, flows going back and forth. They know their distant colleagues well, and feel a closeness despite the distance. They identify themselves as being on the same team.

My advice to organisations with centralised functions in one location? Recognise the complexity and necessary interactions in your organisations. Support the colleagues to develop the knowledge, skills and mindset to work virtually, across cultures and in these global structures. Once virtual colleagues acknowledge the types of communications and interactions they need in spite of the distance, they can engage in the meaningful conversations that make a difference in their work experience.

.png?width=120&height=120&name=RISE%20Logo%20(7).png)

%20(1).png?width=133&height=133&name=Compass%20Coasters%20(87%20x%2087%20cm)%20(1).png)

.png)

.png)